Daisy Rain Martin has never been afraid to promote inclusivity in her classroom.

A longtime language arts teacher at the Vallivue School District’s Sage Valley Middle School, Martin places books on her shelves that reflect the diversity of her classroom. She chooses curricula that inspire her students to think outside the box. And she encourages kids to explore, research and think critically about the world around them.

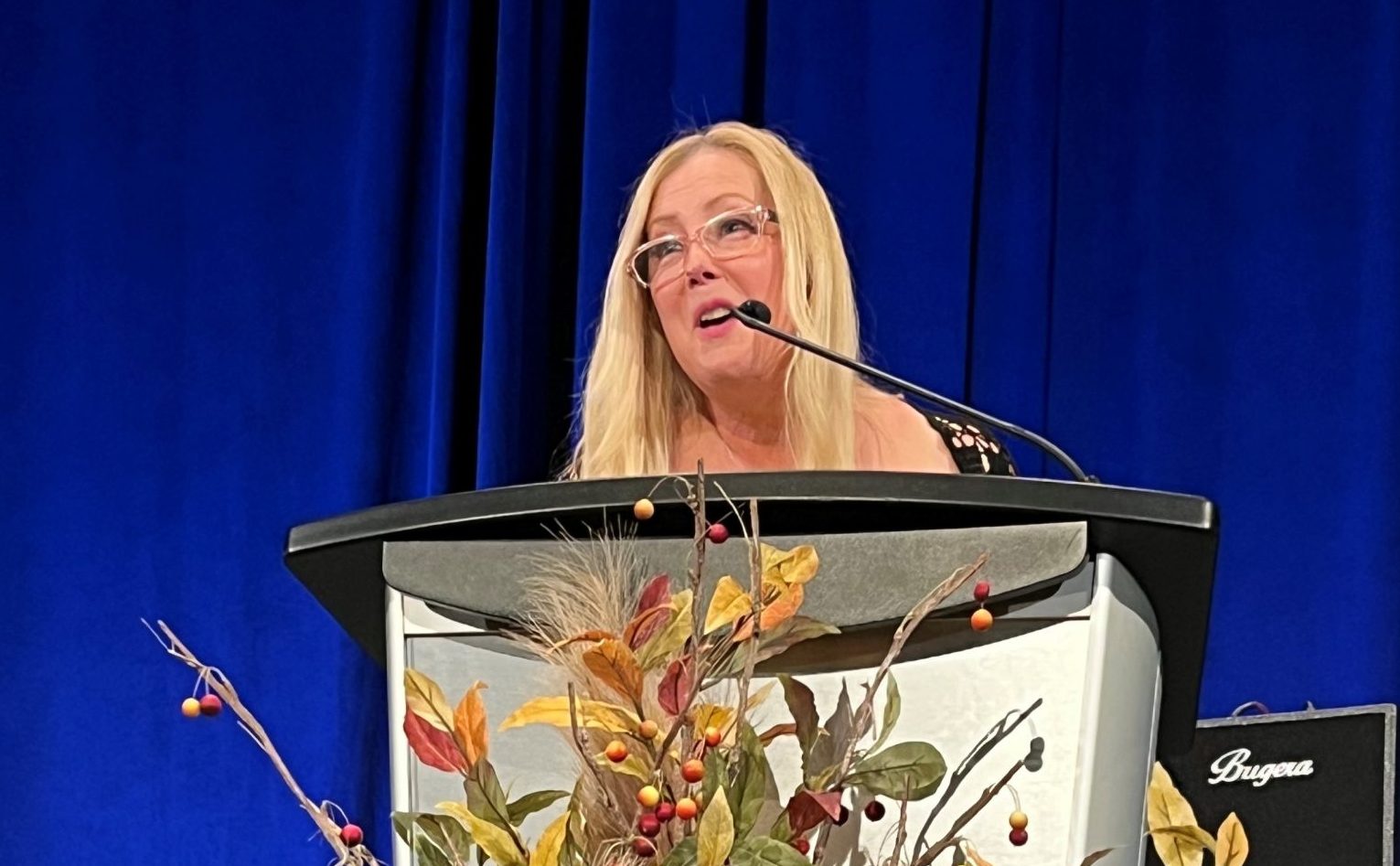

Her efforts have earned her statewide recognition — she’s this year’s recipient of the Human Rights Educator of the Year Award — an accolade awarded by the Wassmuth Center for Human Rights to educators who go above and beyond to ground their classrooms in justice and joy, and honor every person’s dignity.

But as the public education arena grows increasingly polarized, and fraught with political tensions, championing human rights in the classroom has become a controversial act. Some conservatives would see Martin’s teaching philosophy — and her award — as an example of alleged indoctrination in schools.

And with the threat of policies and laws that would censor her in the classroom, and put her at risk of private lawsuits, Martin says she’s had enough. She’s not willing to compromise her values for politics, so she’s taking an early retirement. This is her last year teaching.

“I’m not leaving a bad place,” Martin said Thursday in an interview with EdNews. “I’m leaving a good place, but (retirement) will be a safer place. I won’t feel any pressure to bend to things I know I will not bend to.”

Representation in the classroom is a ‘life or death’ matter, says Martin

Martin’s classroom is filled with diversity — her students come from different countries, different states and different religious backgrounds. Some speak multiple languages. Some are minorities. Some are members of the LGBTQ+ community. As their teacher, Martin knows it’s part of her responsibility to help them all feel valued — if they don’t feel safe at school, learning becomes even more challenging.

So, she focuses on representation. She wants her students to be able to see themselves in the books they read and the materials they study.

But that practice has brought challenges. From course textbooks to the Harry Potter series, Martin has heard complaints from parents who believe certain materials aren’t suitable for their children.

Martin provides free curricular materials for educators in need. Head to her website to learn more.

“Every ELA teacher has had parents push back on certain books for one reason or another and request that their child not read a particular text. They don’t always give us a reason,” Martin said. “Sometimes it’s because they feel the content is too mature for their child. Sometimes people in their religious community admonish them to avoid certain titles.”

So, Martin accommodates those requests — that, too, is a part of helping students feel included in the classroom.

“Parents have always had the right to be involved in what their child reads — it’s their child.”

But the right of one student/family shouldn’t trump the right of another student/family, Martin says. LGBTQ+ students should have access to books with LGBTQ+ characters. Latino students should have access to books with students who look and speak like them and their families. That type of representation can, Martin said, be the difference between life and death.

“I am never going to reject a child. I don’t care who it is demanding or telling me. I’m not doing it.” — Daisy Rain Martin, Idaho’s Human Rights Educator of the Year.

LGBTQ+ youth and minorities are at higher risk for developing depression, anxiety and suicide — especially in middle schoolers, who are already prone to low self-esteem and mental health challenges.

But as lawmakers attempt to place restrictions on what can and can’t be read and said in schools, Martin says educators are sitting in a difficult position.

“We have two choices as teachers: eliminate anything that might bring down the wrath of a stakeholder (which, at the end of the day, includes just about everything) and participate in the erasure of minorities and marginalized kids or…walk around flinchy all the time, waiting for the other shoe to drop,” Martin said.

For Martin, that isn’t a choice.

“I don’t work for adults, I work for kids,” Martin said. “I am never going to reject a child. I don’t care who it is demanding or telling me. I’m not doing it. I am not going to have the blood of a child on my hands. I’m not going to be part of a child’s decision to leave this planet.”

Martin also encourages her students to be inclusive of each other. At the beginning of each year, she challenges her students to a year-long research project — choose one country to research thoroughly. Dive into its government, customs, environment, and myths and legends. The big question she’s asking them: What could we achieve if we looked at the world through someone else’s eyes?

It’s not only a research project — it’s an exercise in empathy. At the end of the year, she wants them to be able to appreciate the country they researched, no matter how different it is from home.

“No matter the form of government…we want kids to know that there are beautiful children just like them and beautiful families just like theirs in every country,” Martin said.

It’s that unfailing commitment to human rights that won Martin the Wassmuth Center’s award.

Jess Westhoff, education programs manager for the Wassmuth Center, said that beyond her work, the overwhelming support for Martin made her stick out — four of her colleagues separately nominated her.

“Her nominators talked about the way that she focuses on creating experiences for her students in the classroom, making sure to connect them with diverse texts, opportunities for them to tell their stories, and explore other people’s stories,” Westhoff said. “But then also she’s such a strong advocate for her students outside of the classroom as well. That was another thing that was really impressive.”

When Martin found out about the award, she was “baffled.” Westhoff, she said, had to tell her four times before she believed it.

“I still cannot wrap my brain around this, but I can tell you that I am incredibly honored,” Martin said.

Martin seeks refuge in retirement because she’s ‘better unfettered’

At the end of this school year, Martin will retire. She’s seeking refuge from legislation and policy that could force her to compromise her values.

Because if the time came, Martin said, she wouldn’t bend to rules that would force her to eliminate books from her shelves, or censor her speech in the classroom.

“I’m better unfettered,” she explained.

During her retirement, she’ll focus full-time on children’s literature — a hobby that has been a side gig throughout her career in education. She already has one manuscript done. She’ll also focus on providing resources to teachers — curricular materials, professional development opportunities and more.

And she looks forward to working with the Wassmuth Center. After she accepted the award at the center’s gala on Saturday, Martin said she felt at home among the group who attended.

“When you’re on the side of love, compassion, mercy, justice, all of these things, it’s easy to feel like you are swimming upstream,” Martin said. “But once you get in a place where everyone loves everyone, and everyone is committed to justice and mercy — you need that. We all need that.”